There are many different circumstances that cause people around the world to flee their homes and seek safety elsewhere. In the complex landscape of immigration, terms like refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants are often used interchangeably, leading to confusion and misunderstanding. While they all share the common goal of finding a new home in a new land, the various types of migrants are distinct, and each is potentially able to access different pathways to achieve their aspirations and goals.

Migrants

The term “migrant” technically just means a person who moves from one place to another for any reason, though it is increasingly used colloquially as short-hand for “economic migrant”—a person who moves primarily to seek better economic opportunities and quality of life. It’s helpful to keep the terminology straight, distinguishing between voluntary migrants and forced migrants. Refugees and asylum seekers are considered forced migrants, involuntarily leaving their homes.

The challenge of any country’s immigration system is to carefully distinguish between voluntary and forced migrants as this determines eligibility for certain pathways to entry, legal protections under international and domestic law, and benefits. Given complex push factors and the large numbers of people on the move, it can be very challenging to make efficient and accurate status determinations for the various types of migrants. Economic motivations alone do not necessarily distinguish economic migrants from refugees, as they can be a symptom of persecution on one of the protection grounds (race, religion, ethnicity, political opinion, etc.), as certain minorities are barred from economic opportunities in some countries.

In the context of United States immigration, voluntary migrants may be eligible to enter through legal channels such as employment-, study-, or family-based visas, or they may enter “unlawfully” and face potential deportation.

Refugees

Refugees are forced migrants who have fled their home country to escape conflict, violence, or persecution and have sought safety in another country (UNHCR). The country to which the refugee has fled is commonly referred to as the host country or country of temporary asylum. “Refugee” is a legally recognized status that affords individuals certain protections while they seek permanent solutions, but can also come with many restrictions. Many refugees spend 20 or more years living in their host country, where they are often unable to legally work, own property, or move freely. In most temporary host countries, children born to refugees living there are not granted citizenship but are also considered refugees (with derivative status from their parents) or are considered “stateless.”

Unfortunately, most refugees are unable to return to their home country in the near term, if ever. When they can’t, they hope to either legally integrate into the host country (which is also often not possible), or find a pathway to another country (often referred to as a third country), where they can safely build a new life for themselves and their families. Many aspire to come to the United States.

Of the 43.7 million refugees across the globe, a very small percentage come to the United States (see the FAQ section below for data). The refugees who are approved to resettle to the U.S. undergo a rigorous vetting process including background and medical checks. They are granted refugee status prior to entering the country, so that upon entry, they immediately have legal rights and are on track to become permanent residents and eventually citizens, allowing them to rebuild their lives in safety and with dignity.

Read more about how RefugePoint partners with refugees to find lasting, life-changing solutions.

Asylum Seekers

Asylum seekers are similar to refugees in that they, too, flee their home countries and seek safety in a foreign land. However, unlike refugees, whose status has been determined prior to entering the country, asylum seekers request asylum after arriving in the country. They present themselves to immigration authorities and undergo a screening process that determines whether they will be allowed to stay.

The screening process and legal frameworks for asylum seekers vary by country. If granted asylum, they are typically afforded similar rights and protections as refugees, which in the United States includes the opportunity to work, go to school, rebuild their lives, and eventually naturalize as citizens.

While refugees and asylum seekers often face prejudice and stigma in the United States, they have a net positive effect on both their local and national economies. A recent study by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that refugees and asylum seekers contributed a net $124 billion to the economy between 2005 and 2019.

RefugePoint’s Work

At RefugePoint, we work with refugees who have fled their homes and are living in host countries (click here to see a map of where we work). For refugees who are stuck in their host country without an opportunity to return home or access resettlement or another pathway to safety, we help them leverage their available resources to achieve self-reliance and become independent. For those who aren’t safely able to stay in their host countries, we help refugees access available legal pathways like resettlement, labor mobility, and family reunification to find safety in a third country.

FAQs

Is the crime rate among refugees, asylum seekers, and undocumented migrants higher than for U.S. citizens?

No—in fact, the opposite is true. According to a large and growing body of local, state, and national research, refugees and asylum seekers commit crimes at lower rates than U.S. citizens. Furthermore, studies have shown that these groups also do not raise crime rates in areas where they live; in fact, one study found that cities with high immigration enjoyed lower homicide rates over time.

Undocumented migrants also commit crimes at lower rates than U.S. citizens. According to the Migration Policy Institute, “While being present in the United States without authorization represents an administrative infraction (punishable by removal), unauthorized immigrants are less likely to commit misdemeanor and felony crimes than the U.S.-born population and other immigrant groups.”

I’ve recently heard about “climate refugees.” Are these individuals treated the same as refugees in the eyes of the law?

No, they are not. It is important to note that “Climate Refugees,” a colloquial term describing those who have been displaced due to the growing effects of climate change, are not considered refugees in the eyes of international law (unless the displaced person has also been the subject of persecution as defined by refugee law) and are generally not able to access the same pathways or protections as refugees. It is worth noting that climate change can trigger or exacerbate conflict, so there are often complex interconnected reasons why people are forced to flee their homes. It is an emerging area of refugee law to establish a precedent for climate-related claims that amount to persecution. Some examples include minority groups that are excluded from government aid in response to climate disasters for political or ethnically-motivated reasons, and also environmental activists targeted by their own governments.

What is humanitarian parole?

Humanitarian parole is a discretionary measure used by the U.S. government that is designed to allow foreign individuals to urgently enter the United States in exceptional circumstances, such as for medical treatment or to attend a relative’s funeral. Unlike the refugee admissions process, humanitarian parole does not offer permanent status (although in some cases, permanent status can later be acquired). Traditionally, humanitarian parole was used only rarely, for very few individuals, in the exceptional circumstances described above. More recently, the use of humanitarian parole has increased as an urgent response to people fleeing sudden danger in places such as Afghanistan and Ukraine, as other pathways such as the U.S. refugee admissions program would take too long. However, many advocates would prefer to see the pace of refugee resettlement accelerated rather than an ongoing broad use of humanitarian parole as a substitute rescue pathway, since the beneficiaries do not enjoy the same rights of residency and assistance after arrival.

How many refugees are admitted into the U.S. each year?

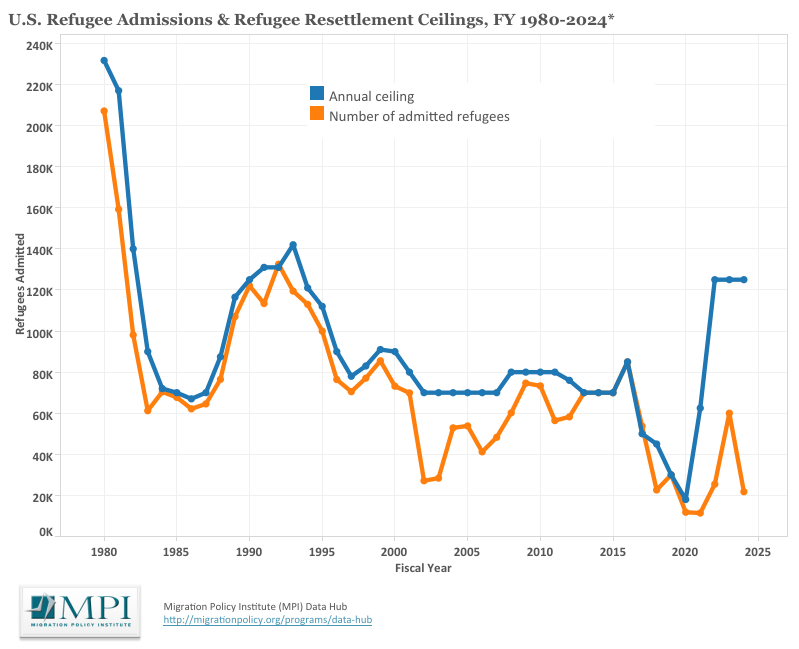

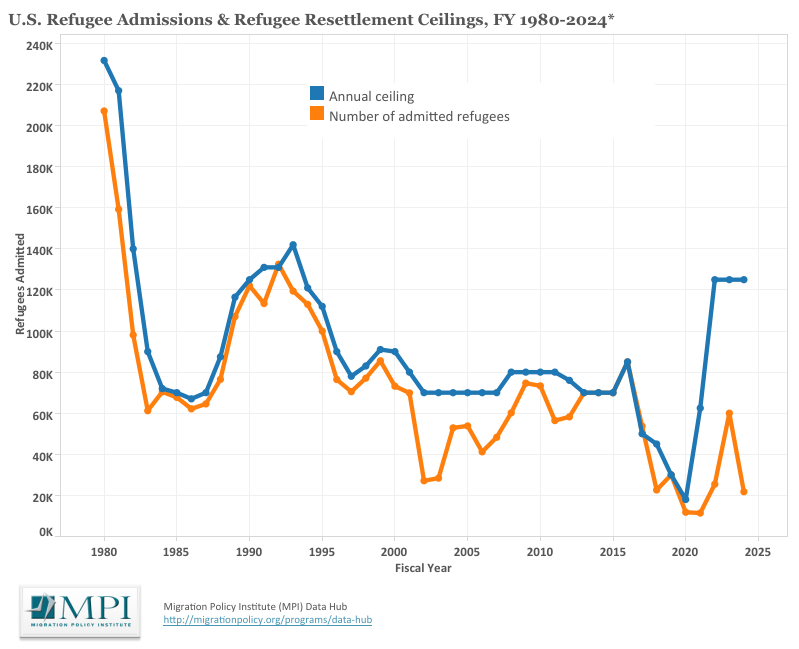

In consultation with the Department of State, the Department of Health and Human Services, and Congress, the President makes an annual determination of the number of refugees the U.S. agrees to admit each year. Click here and here to view U.S. annual refugee admissions ceilings and actual refugee admissions by year from 1980-present. In fiscal year 2024, the U.S. admitted 100,034 refugees. The ceiling set for 2025 is 125,000, though the incoming administration is likely to reduce this number drastically.

*According to UNHCR, there are currently 35.4 million refugees worldwide, but the total amount of forcibly displaced people globally is currently over 114 million.

By Alison Pappavaselio, Digital Communications Officer, RefugePoint

RefugePoint envisions an inclusive world where all refugees can safely build stable, connected, and thriving lives. Our Theory of Change (ToC) shows how we’re turning that vision into action. The...

Over the past year, the world has shifted in ways that have made life far more dangerous and uncertain for refugees. Support systems that once offered stability are eroding: global...

This week marks the 2025 Global Refugee Forum Progress Review in Geneva, Switzerland: a time for the international community to take stock of our progress on the pledges that we...

![Refugees, Asylum Seekers, and Migrants: What’s the Difference? [Updated for 2025]](https://refugepoint.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Medical-00759-CJ-1.jpeg)