By Kellie Leeson and Ilana Seff

Jane,* a Congolese refugee, lives in a small, tidy apartment on the outskirts of Nairobi, Kenya with her husband, two small children, and adult brother. Her brother sleeps during the day so he can work the night shift and her husband spends most of his time in another city due to security concerns in Nairobi. Both of Jane’s children attend school. Her family is lucky to have plumbing and access to running water; while the facilities are shared, there are few other tenants in her building. Jane hopes to start a small business and has already built relationships with her potential suppliers. Unfortunately, Jane has not earned enough to invest in her plans. The family remains stuck on a monthly treadmill, barely able to keep up with their rent.

Meanwhile, on the outskirts of Amman, Jordan Layla* lives in a two-room dwelling with her adult son. Layla recently attended a business development class and is now selling handmade soaps and small trinkets. While her business is still nascent, she is optimistic. Her grown son has chronic health issues and unreliable access to affordable health care, making him unable to hold a steady job. Layla depends on food vouchers from the World Food Programme for sustenance. She and her son struggle to pay the rent, but they are lucky to have a patient landlord and have not yet been evicted.

—————————————————-

We encountered both of these households on recent trips to the two countries, where we were tasked with answering one key question: How do you measure a refugee household’s level of self-reliance?

Answering this question is no easy endeavor; a myriad of social, political, and economic factors can contribute to self-reliance, and these dynamic determinants may change by the month or even day. However, although measuring self-reliance is a difficult task, it is a critical one; and, it is precisely for this reason that the Refugee Self-Reliance Initiative (RSRI) has commited to developing a tool to do so.

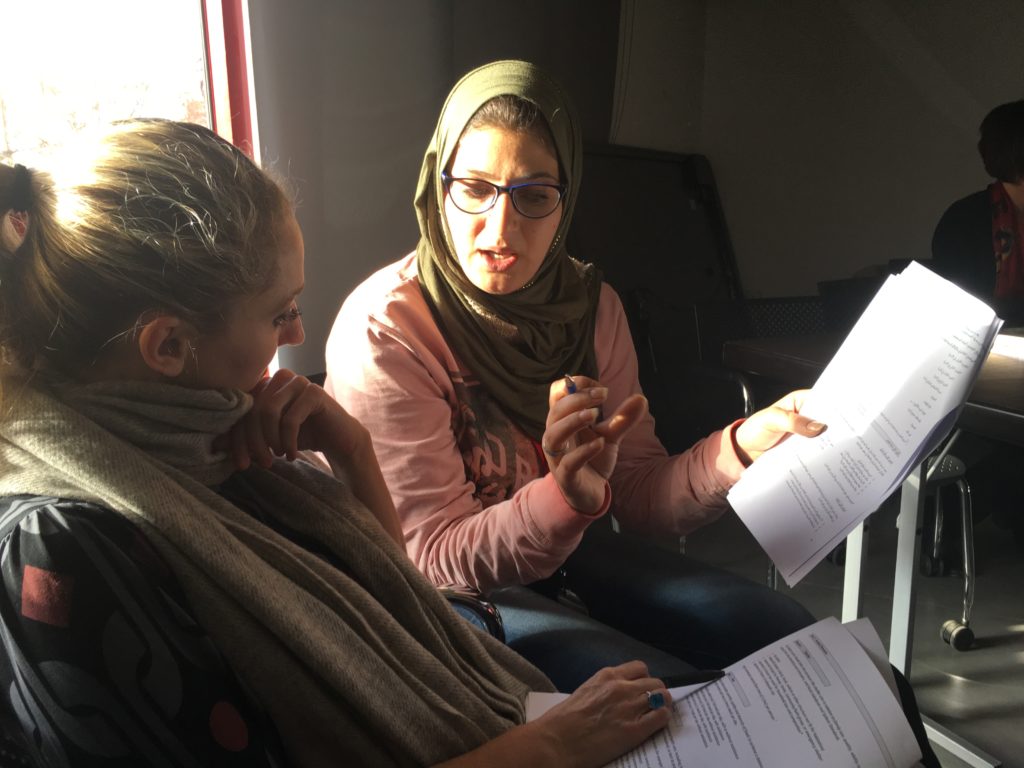

In 2016, a refugee self-reliance community of practice comprised of more than 15 organizations across the globe was convened to better understand and share learning on this topic. The work of this community laid the foundation for the wider Refugee Self-Reliance Initiative (RSRI) that is committed to identifying and supporting practical approaches that will enable refugees to sustainably meet their own essential needs. In 2017, this community began developing a measurement tool – the Self-Reliance Index – an easy-to-use tool that tracks households’ progress toward and achievement of self-reliance over time. Building on the UNHCR definition of self-reliance, the RSRI defines the term as “the social and economic ability of an individual, a household or a community to meet its essential needs in a sustainable manner.” Co-created by the RSRI community of practice, the Self-Reliance Index is currently being piloted in Jordan, Kenya and Mexico with Mercy Corps, Danish Refugee Council, RefugePoint and Asylum Access. The International Rescue Committee in Kenya also tested and adapted earlier versions of the tool. These vastly different contexts allow us to observe how the tool fares across distinct environments, populations, languages and program settings.

In this most recent phase of the pilot, we tested the tool with refugee families in Jordan and Kenya, allowing us to observe how the tool was utilized by case workers and how it was understood by refugees. Jordan and Kenya are both home to large protracted refugee situations. The Syrian conflict began in 2011/2012 and, according to UNHCR, Jordan is host to 690,000 Syrian refugees. Only approximately 120,000 of these refugees live in camps, meaning the vast majority live in towns and cities throughout Jordan. In addition to this large Syrian population, Jordan is also host to Iraqi and Palestinian refugees. In Kenya, the refugee profile is much more diverse. As of December 2018, UNHCR estimated Kenya was host to approximately 470,000 refugees, with the majority having fled Somalia, Congo, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Rwanda, Eritrea, Burundi, and Uganda. Many of these refugees have lived in Kenya since 1992, but recent waves of migration have occurred from Burundi, Congo and South Sudan.

To maximize adoption of the Index by the already time-pressed refugee organizations on the ground, we worked to keep the tool compact; the current version of the Self-Reliance Index encompasses just twelve domains: housing, food, healthcare, health status, education, employment, income, savings, debt, security, social capital, and initiative. Recognizing the value of keeping the tool simple, we must still ensure these twelve domains are broad enough to capture the core elements of self-reliance and nuanced enough to be relevant to the vast contextual differences of the lives of refugees we seek to support. Rather than asking what we want to know, we realize we must instead reflect on what we need to know.

Overall, the tool resonated with clients in both pilot sites, but interesting differences between the two sites emerged for some domains. For example, while refugees in Jordan were quick to share examples of “bridging social capital” (i.e. social relationships with the host population), refugees in Kenya shared that they had minimal meaningful contact with Kenyans and were much more likely to draw on “bonding social capital” from their fellow refugees. Contextual variation in the nature of social capital may relate to other differences we observed in perceptions of safety and utilization of debt. The predominant security concerns voiced by refugee families in Jordan typically related to housing instability and gender-based street harassment or threat of violence. Households in Kenya instead reported constant fear of harassment, extortion and arrest from Kenyan police. In Jordan, nearly every household we interviewed held a debt of some type, most often taking the form of extended credit from a local grocer or unpaid rent. In contrast, we found almost no cases of debt in Kenya, where aggressive collection networks made refugee households unwilling to take debt, no matter how dire the situation.

Despite these nuanced differences, the similarities we observed highlighted some of the biggest expected obstacles to achieving self-reliance. In both countries, we noted the significant toll that lack of health care, including for mental health issues, took on refugee families. The mental health issues we came across were not only severe in nature (for example, individuals exposed to severe trauma, loss, and/or torture), but were also considerably debilitating and compromised the ability of the distressed to become self-reliant by rendering them unable to performs daily tasks, care for their children, or obtain work.

Next month, we plan to test the Self-Reliance Index in one final setting with refugees from Central America currently living in Mexico. As we continue to adapt the tool and improve its validity and reliability across multiple contexts, we hope to simultaneously generate insight into the most important ingredients for refugee self-reliance and provide practitioners a road map for supporting this path. As crises become increasingly protracted, the humanitarian community will need to continue shifting its focus to ensuring the necessary systems are in place to promote refugees’ self-reliance and ability to thrive even when durable solutions remain elusive. We hope the Self-Reliance Index can help these humanitarian actors track their success in achieving this objective over time and hone the effectiveness of their programming. When transformative models of humanitarian and development aid enable Jane, Layla, and their families to sustainably rely on themselves and fulfill their aspirations, we want to be there to celebrate (and measure) it.

*Not her real name